Welcome to our virtual exhibition on the contribution of Dr. Armand Frappier and the Institute of Microbiology and Hygiene of the University of Montreal in Canada’s war effort during World War Two.

The pre-war years

In the Province of Quebec, before World War Two, there is a desire to modernize scientific research, as there is no institution dedicated to microbiology, bacteriology or hygiene. As a result, Quebec has to rely on external sources for its vaccines and other biological products..

One man is about to change all this. With the determination and energy that will become his trademark, Dr. Armand Frappier rallies the provincial government on the idea of creating and funding a Quebec organization that would shine at home and abroad. With war looming on the horizon, this institution will consolidate its status by taking part in the Canadian war effort.

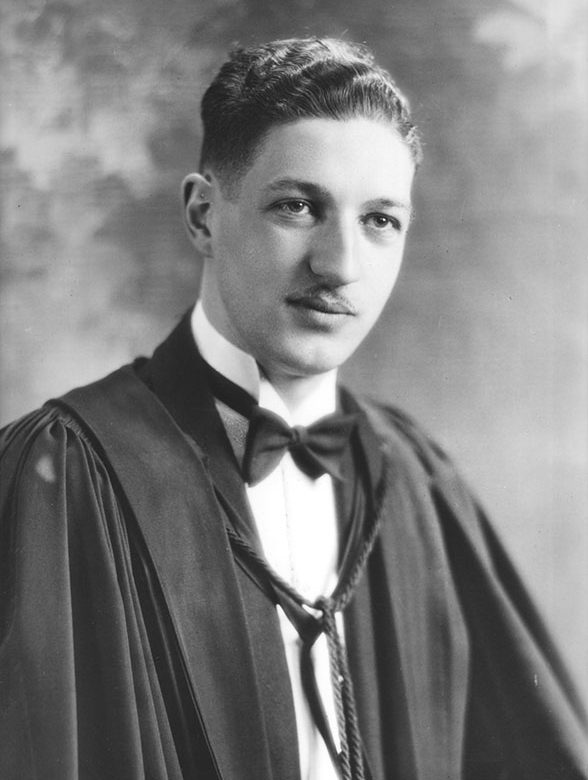

Biography Dr Armand Frappier

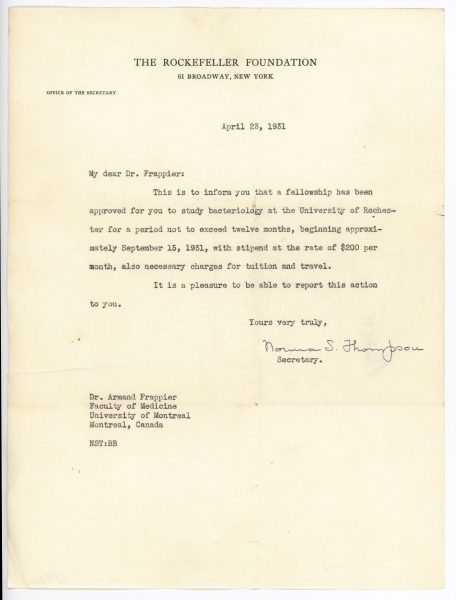

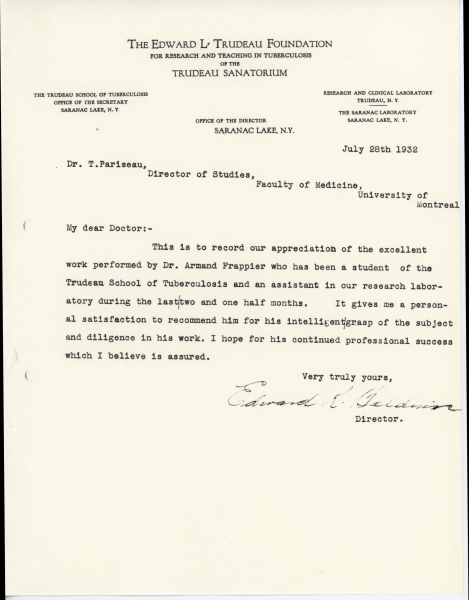

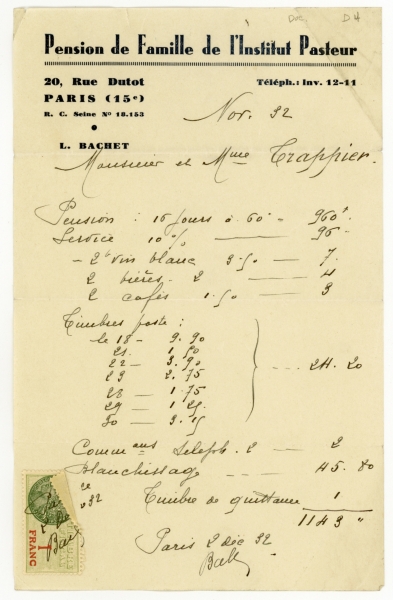

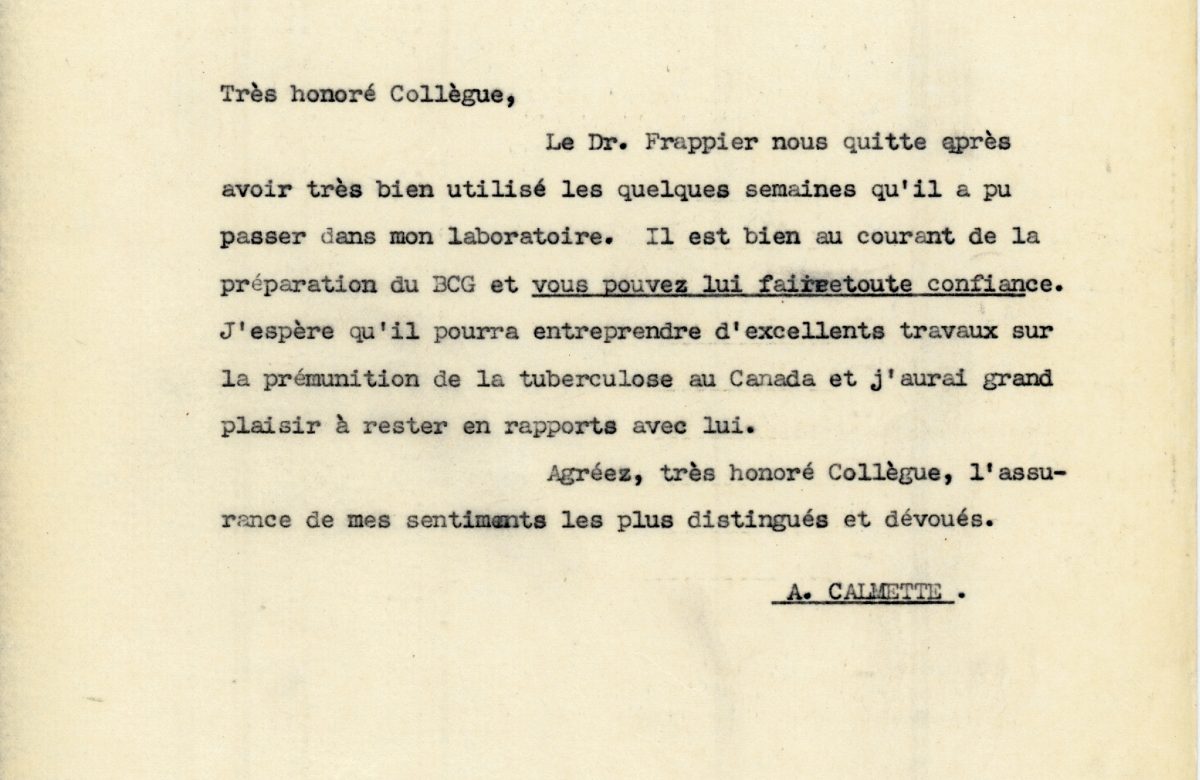

Armand Frappier was born in 1904 in Salaberry-de-Valleyfield. He chose medical studies after the death of his mother to tuberculosis. She was only 40. His medical studies completed, he specialized in bacteriology (from which microbiology would evolve). Thanks to grants such as one from the Rockerfeller Foundation, and because no such training is available in the Province of Québec, Dr. Frappier began graduate studies abroad. Young Dr. Frappier trained in prestigious American institutions, such as the Trudeau School of Tuberculosis (University of Rochester). But above all, he studied at the Institut Pasteur in Paris. It is there he will rub shoulders with Dr. Albert Calmette, Camille Guérin and Léopold Nègre, the famous discoverers of the BCG tuberculosis vaccine. It is an attenuated strain of this vaccine that Dr. Frappier brings home with him.

Upon his return, the career of Dr. Frappier begins auspiciously.

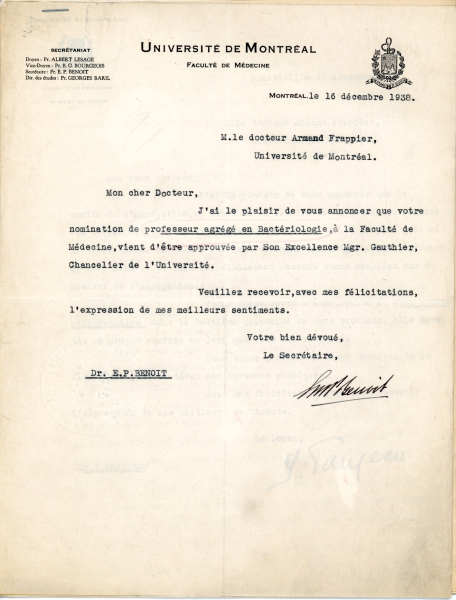

He is the founder of the diagnosis laboratory of St-Luc Hospital in Montreal. He also became assistant professor in the Bacteriology Department, a part of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Montreal.

With the support of Dr. Télesphore Parizeau, the Dean of the Faculty of Medicine, he leads the first BCG laboratory in North America (founded in 1926) in order to experiment and prepare the vaccine against tuberculosis. Dr. Armand Frappier will be among the first scientifics in North America to prove the safety and effectiveness of the BCG vaccine to his colleagues.

Quebec Government and the University of Montreal

The University of Montreal and the Quebec Government exerted a strong influence on the Institute of Microbiology and Hygiene of the University of Montreal. First, the Institute traces its roots back to the Bacteriology Department, which was managed by Dr. Frappier and was part of the University’s Faculty of Medicine. This is where the Institute’s team was formed and also where originated the idea to create an organization dedicated to microbiology, preventive medicine and public health.

The Province of Quebec had a need to train experts in these fields. It also needed modern laboratories, and to produce its own vaccines instead of buying them abroad or in Ontario from the renowned Connaught Laboratories in Toronto. Dr. Frappier wanted to update scientific research in Quebec.

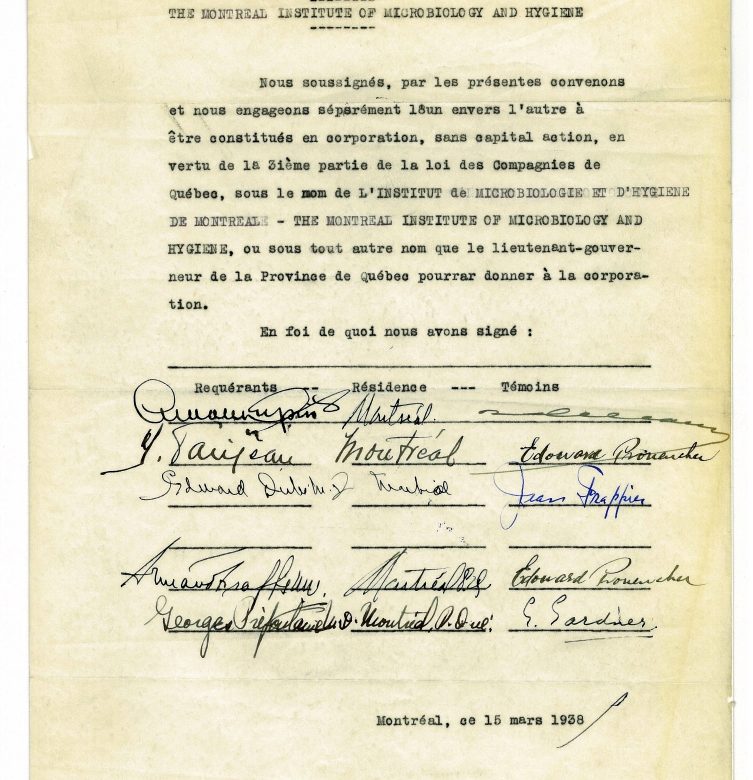

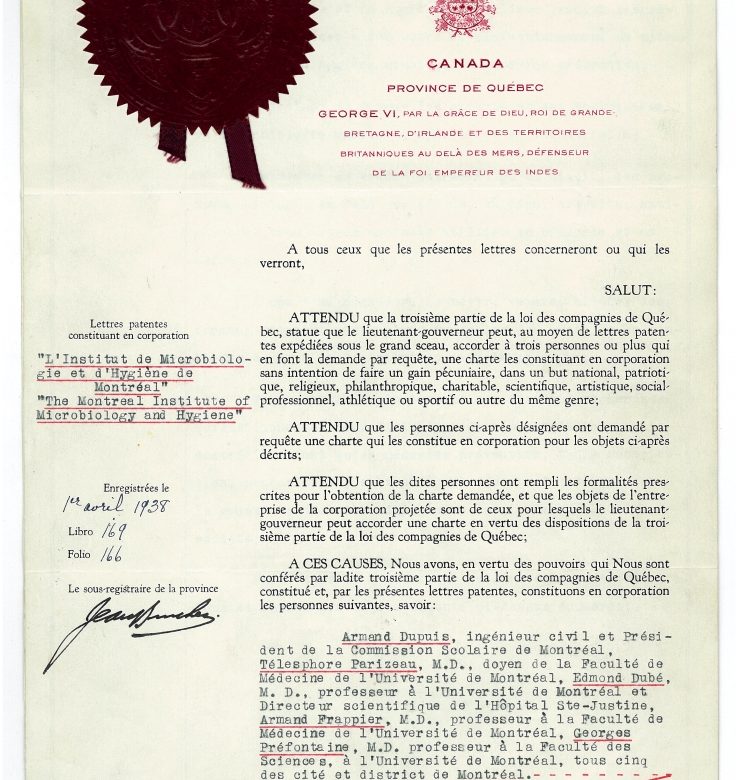

Based on the Institut Pasteur model, he worked to make it self-reliant through the sale of its production. In 1937, Quebec Premier Maurice Duplessis and the Minister of Health, J. A. Paquette, who both favoured Dr. Frappier’s project, granted the initial funds for the creation of the Institute and pledged their help for its development, something they kept on doing as years passed by. The Institute of Microbiology and Hygiene of the University of Montreal was born in April 1938 as a non-profit corporation without share capital. After two years of talks, the University agrees to rent the Institute spaces in its future buildings on Mount Royal. Thanks to the financial support of the University of Montreal and the Quebec Government, the Institute of Microbiology settled in Wing H on May 1941. By a special Act in 1942, it was affiliated with the University and became the Institute of Microbiology and Hygiene of the University of Montreal.

Institute of Microbiology and Hygiene of the University of Montreal

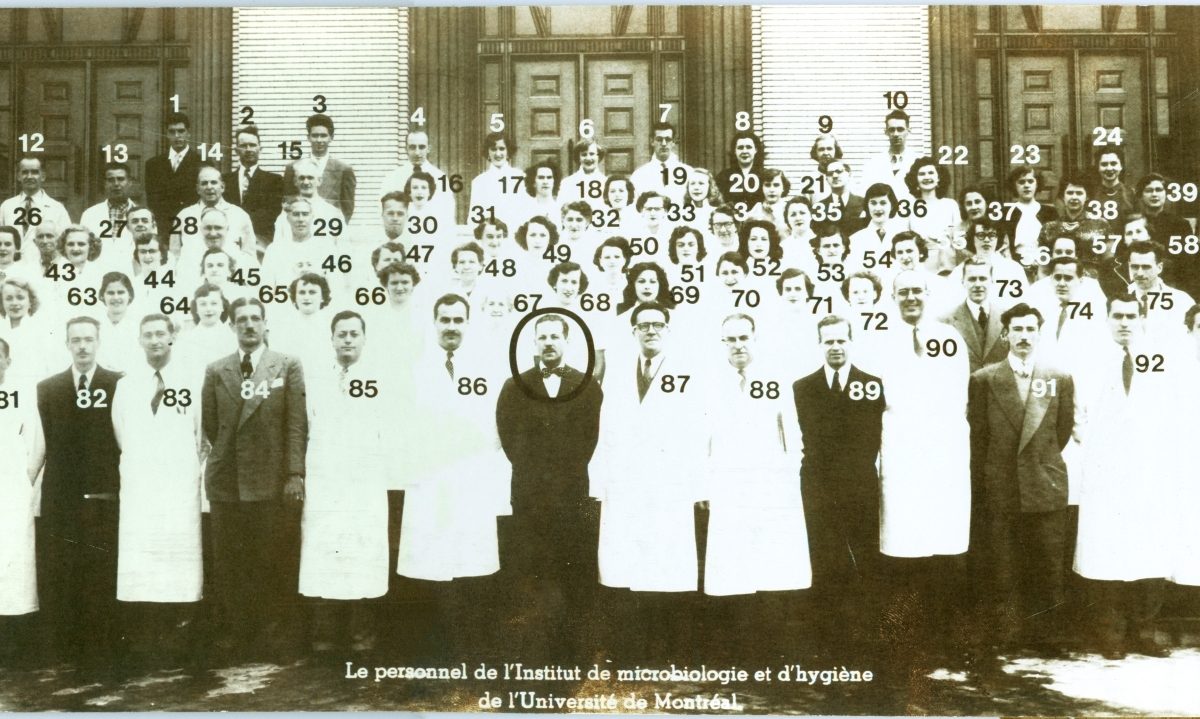

The Institute of Microbiology and Hygiene of the University of Montreal is mostly indebted to its scientific experts for its success. From the beginning, they ensured that Dr. Frappier’s dream would become a reality. From 1934–1935, Dr. Frappier was assisted by students, medical doctors and veterinarians, who became part of the first science cohort of the Institute of Microbiology. Most of them studied in the United States or in Europe, like Dr. Frappier, or in renowned institutions like St-Luc Hospital in Montreal or l’École vétérinaire d’Alfort in France. Amongst them were people like Victorien Fredette, Dr. Frappier’s first assistant, Lionel Forté, Jean Tassé, Maurice Panisset, Jean Denis, Vytautas Pavilanis, Paul Marois and Adrien Borduas.

With the passing of the years, the Institute’s growing team built its strength on the complementary nature of its activities, as shown by the establishment of various research services.

The Microbiology, Public Health and Preventive Medicine Research Service brought together complementary and multidisciplinary departments, amongst which appeared the BCG Service, the Diphtheria Service, the Vaccination Service or the Human Serum Drying Service.

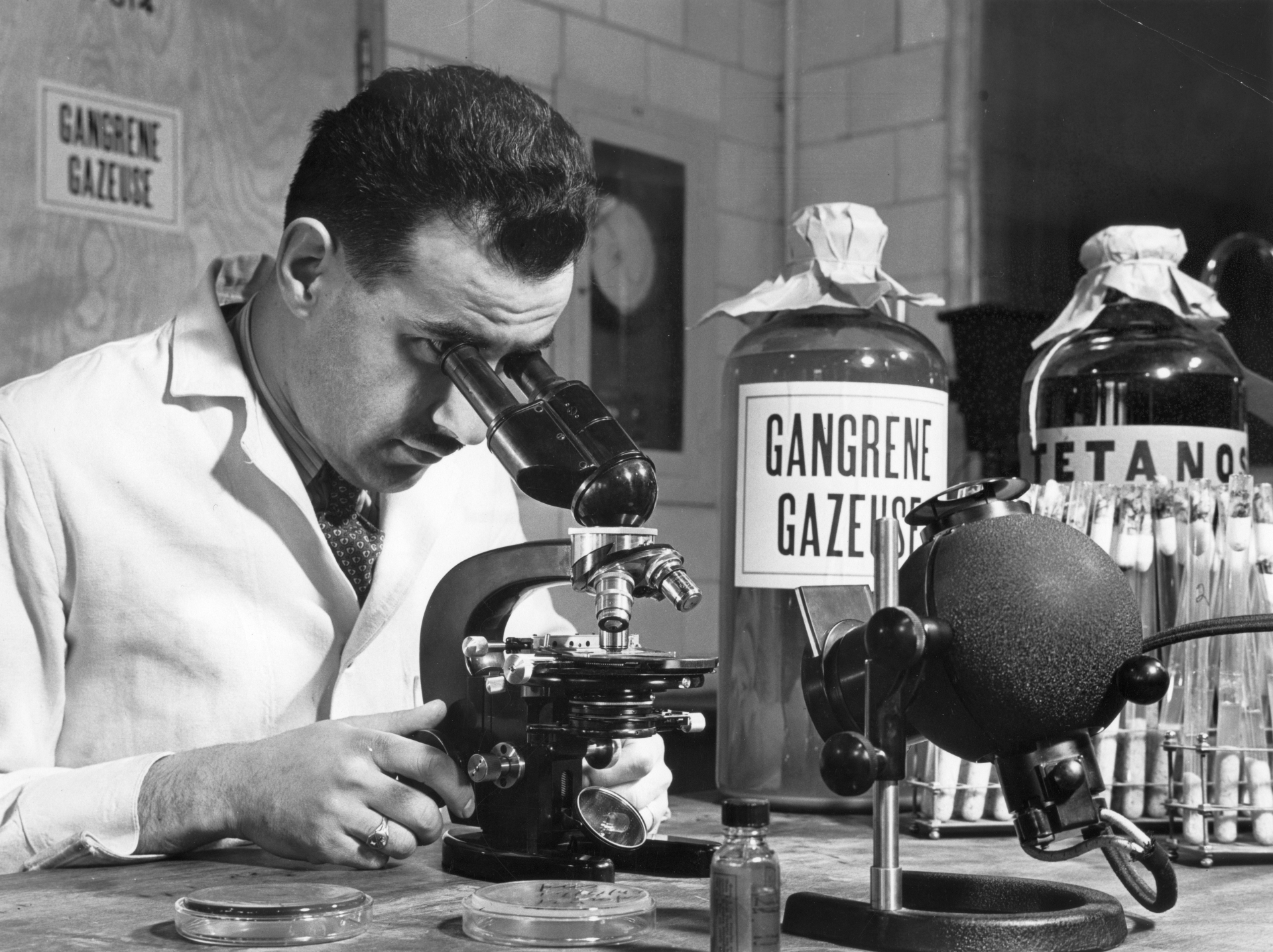

Victorien Fredette, in the anaerobic laboratory, in 1947. Source : Institut Armand-Frappier Fonds The BCG laboratory around 1954. Source : Institut Armand-Frappier Fonds

These services worked in such different fields as experimental tuberculosis, smallpox, gas gangrene or the preventive effects of the BCG vaccine in the treatment of leukemia. All of these numerous research areas will produce a large number of biological products such as the BCG vaccine, diphtheria and tetanus toxoids, normal horse serum or antivariolic and antityphoid vaccines. Some of the Institute’s departments were preparing biological products and others were dedicated to microbiology teaching or to preventive medicine missions, such as BCG vaccination.

The knowledge, dedication and productivity of the staff chosen by Dr. Frappier will contribute to the undeniable reputation of the Institute of Microbiology on a regional, national and international level.

War effort

War is very much a matter of equipment: weapons, ammunition, radio equipment, oil to power the engines of airplanes, tanks and submarines. But war is mostly a “human” matter. Soldiers must be fed, clothed, provided with footwear and even kept motivated. But above all, they must be cared for when they fall on the battlefield.

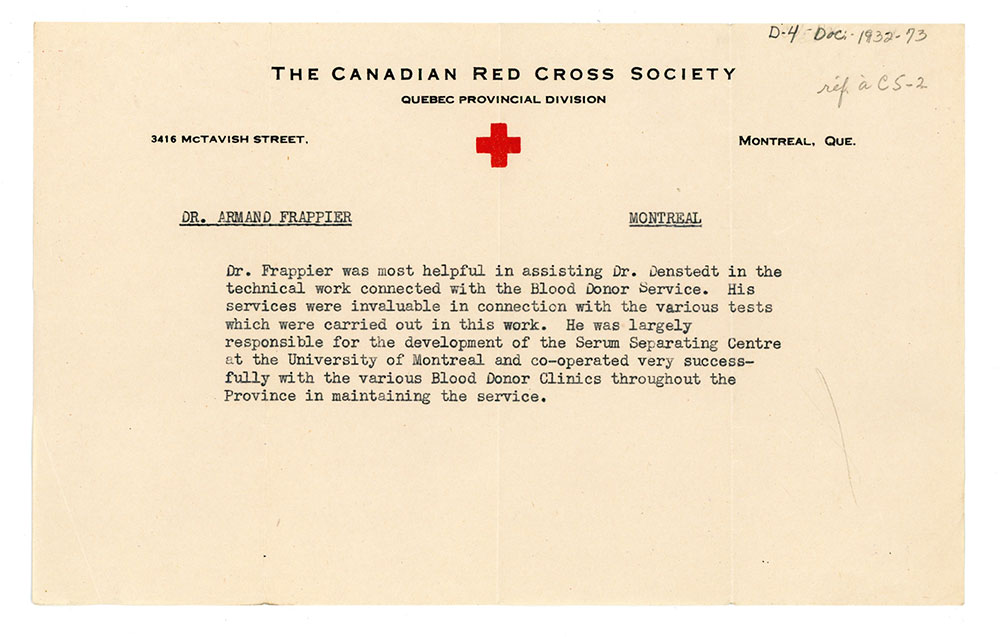

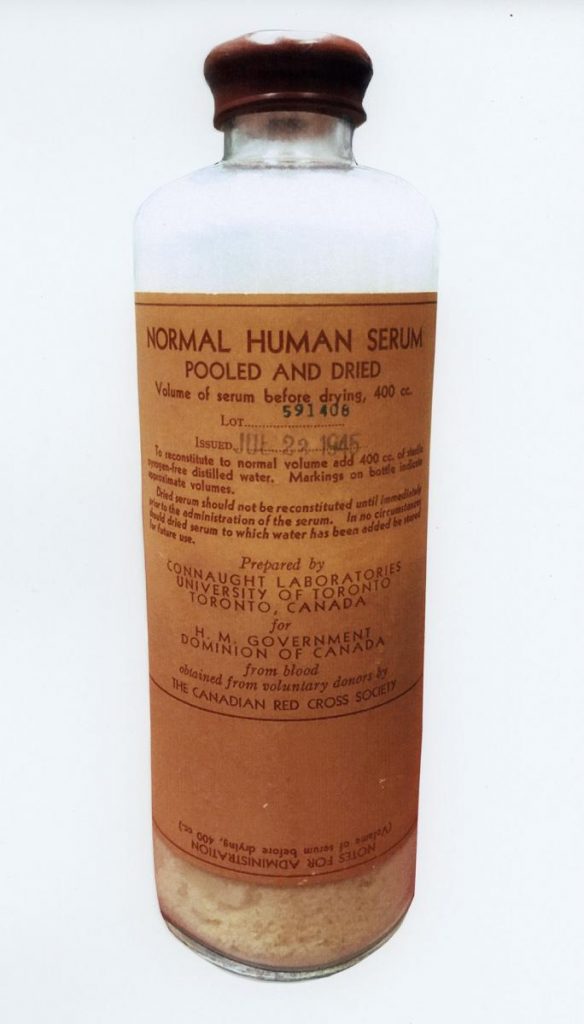

It is in this area that Armand Frappier will shine. With his team and the support of the Canadian Red Cross and the Government of Canada, he will gear up his young Institute for the Allied war effort. In very little time, large quantities of supplies are sent to care for the wounded in Europe, including thousands of bottles filled with dried human serum. It is this tremendous achievement that we want to share with you.

General situation

At the outbreak of World War II, Canada intended to set up its military medical services to anticipate the numerous injured servicemen soon-to-come from war zones. As large blood supplies were going to be needed, The National Research Council of Canada set up research committees on blood preservation and storage and also on blood substitutes in order to determine which strategy was best for the country.

Poster produced by the Red Cross during World War Two. Source : Canadian Red Cross Archives Canadian Liquid human serum vial for emergency transfusion. Source : Institut Armand-Frappier Fonds Canadian Red Cross workers on the packing line. Source : Canadian Red Cross Archives

Late in 1940, Canadian authorities chose to produce normal human serum, a blood derived substitute, according to the experiments led by Dr. C. H. Best at the University of Toronto. Since a lot of blood was required for its preparation, they organized the first national blood donation program. Specialized clinics were developed by the Canadian Red Cross Society, which took charge of blood donations across the country. These were made on a voluntary basis and without any compensation. Blood donations were then sent to Toronto to be processed and transformed into liquid and dried human serum by the Connaught Laboratories. Afterward the serum was forwarded to the battlefronts for the benefit of the Canadian and Allied soldiers.

It was not long before authorities realized that government-subsidized laboratories in Toronto would not be able to cope with the surge in blood donations. Thus emerged the prospect of another blood processing centre.

According to the Red Cross and some of its committees, including the Blood Donor Service Committee, establishing this service in the eastern part of Canada was a wise decision to handle blood donations from this part of the country. The Institute of Microbiology and Hygiene of the University of Montreal thus became the perfect candidate.

Institute of Microbiology and Hygiene of the University of Montreal

According to Dr. Frappier the young Institute of Microbiology was about to play a major part in Canada’s war effort. Indeed, the Institute already had many benefits on its side, such as the expertise from Dr. Frappier and his colleagues, all the research they conducted especially on the BCG vaccine, the trust and research grants they received from the National Research Council of Canada, and also the support from the University of Montreal which accommodated the new laboratories of the Institute of Microbiology. All of these assets proved to be decisive for the patriotic involvement of the Institute.

From the end of 1941, the Canadian Red Cross Society advised the federal government to allow the opening of a second Canadian centre to process blood in order to avoid a shortage of serum and also to relieve the Connaught Laboratories of Toronto, which were then processing all blood donations in Canada. Moreover, a processing centre in the eastern part of the country could be, at that time, in charge of collecting blood donations coming from the Province of Quebec and the Maritimes. For the Canadian Red Cross, this centre could only be the Institute of Microbiology as it had all technical conveniences as well as a strategic geographical position.

But they had to wait for another year and for the intercession of the former Prime Minister of Canada, Richard Bedford Bennett, before the Department of Pensions and National Health could authorize a second centre to process blood for the soldiers’ needs. The Connaught Laboratories also gave the Institute of Microbiology some technical and practical help. Afterwards, the Montreal Institute first began to separate serum from blood in October 1943, before taking care of the whole process up to the desiccation of the serum later on, as it was done in Toronto. The production of dried human serum only began in March 1944 due to long delays with the shipping of the laboratory equipment, which caused increasing costs. Dried serum was all ready to be dispatched by September 1944.

During World War II, one of the many medical challenges was to save as many soldiers as possible.

Blood and its substitutes

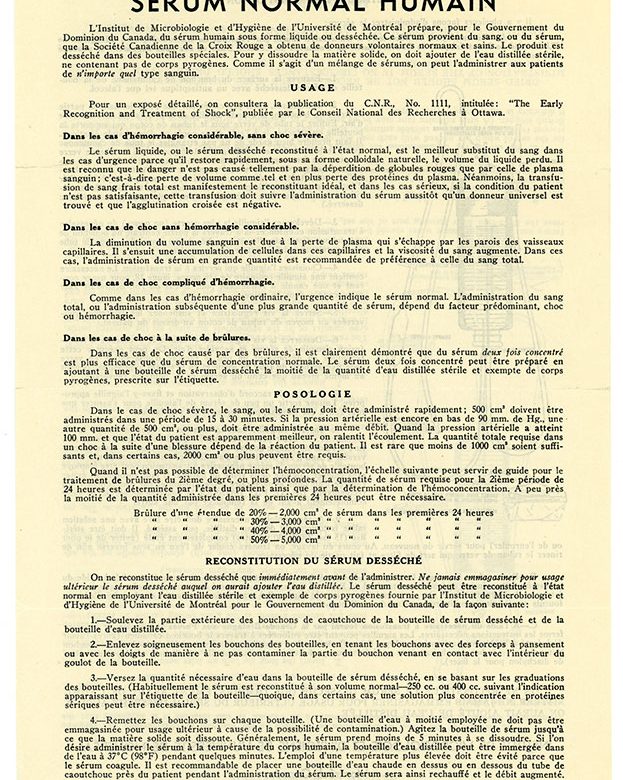

During World War II, one of the many medical challenges was to save as many soldiers as possible. Therefore large amounts of blood had to be stored nearby. However, life-saving procedures such as blood transfusion had their share of hindrances. In case of serious injuries, this technique enabled patients’ blood volume to be restored. However, in the 1940s, blood type matching was not yet fully understood and could result in some tragic transfusion failures, even amongst supposedly compatible patients. Back then, blood preservation was time-limited and depending on weather conditions, could only be stored no more than two weeks. Its transportation and storage being difficult, scientists saw a solution in blood substitutes, such as plasma or serum.

Unlike blood, plasma and serum did not cause any mismatch between donors and recipients, as they were deprived of blood cells, which could provoke immune reactions. Thus, in the late 1930s, committees were set up to study blood substitutes in Great Britain, in the United States and in Canada, where Dr. Best, from the University of Toronto took responsibility for the experiments. Plasma and serum were chosen over blood and began to be mass-produced. Besides, they used a new lyophilization technique to freeze-dry blood substitutes thanks to the combined actions of low temperature and vacuum. These products were lighter than whole blood and easier to carry to the battlefields. Moreover, plasma and serum could last for an extended period of time and could be put in storage through any environmental conditions. Once sterile water was added, they were ready to be injected into the patients. In the same way as blood did, they restored blood volume that was lost by the wounded and prevented traumatic shock.

Connaught Laboratories

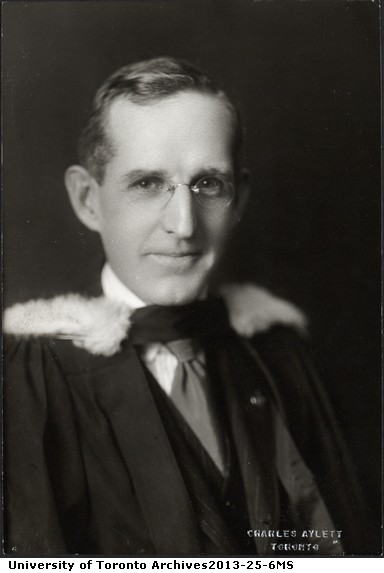

The Connaught Medical Research Laboratories of the University of Toronto shared many objectives with the Institute of Microbiology. Founded in 1914, these laboratories aimed to foster research and education in preventive medicine and public health.

One of the buildings forming part of the Connaught Laboratories in the 1940s. Source : Sanofi Pasteur Canada Archives Production equipment at Connaught Laboratories. 1923. Source : University of Toronto Archives

Following the Institut Pasteur of Paris as a role model, the Connaught Laboratories managed to finance their research and education programs by the production and sale of biological products, a method that also inspired the Institute of Microbiology.

Carrying on the research performed by Dr. C. H. Best of the University of Toronto, the Federal Government and the Canadian Red Cross Society helped the Connaught Laboratories with the production of dried human serum for the Canadian and Allied soldiers, as soon as January 1941. The blood donations required for the production of human serum never ceased to increase during the war, compelling the Connaught Laboratories to expand several times their war effort facilities and to acquire new equipment to boost productivity. Alongside the dried human serum production, they also prepared penicillin for the Canadian Army. Nevertheless, the Connaught Laboratories always maintained their production of other biological products, such as the typhoid-paratyphoid vaccine or insulin and they still conducted research in preventive medicine and public health.

Throughout the war, the Toronto laboratories carried out a high rate of productivity as shown by the figures of 1944. During that year, the Connaught Laboratories received 868,684 blood and serum donations to process. As a result, 184,436 bottles of dried human serum were shipped to Ottawa’s medical supplies or directly overseas, in Great Britain. After the war, they kept up their research and development activities by working, among other things, on blood fractionation and poliomyelitis treatment.

Mentors and partnerships

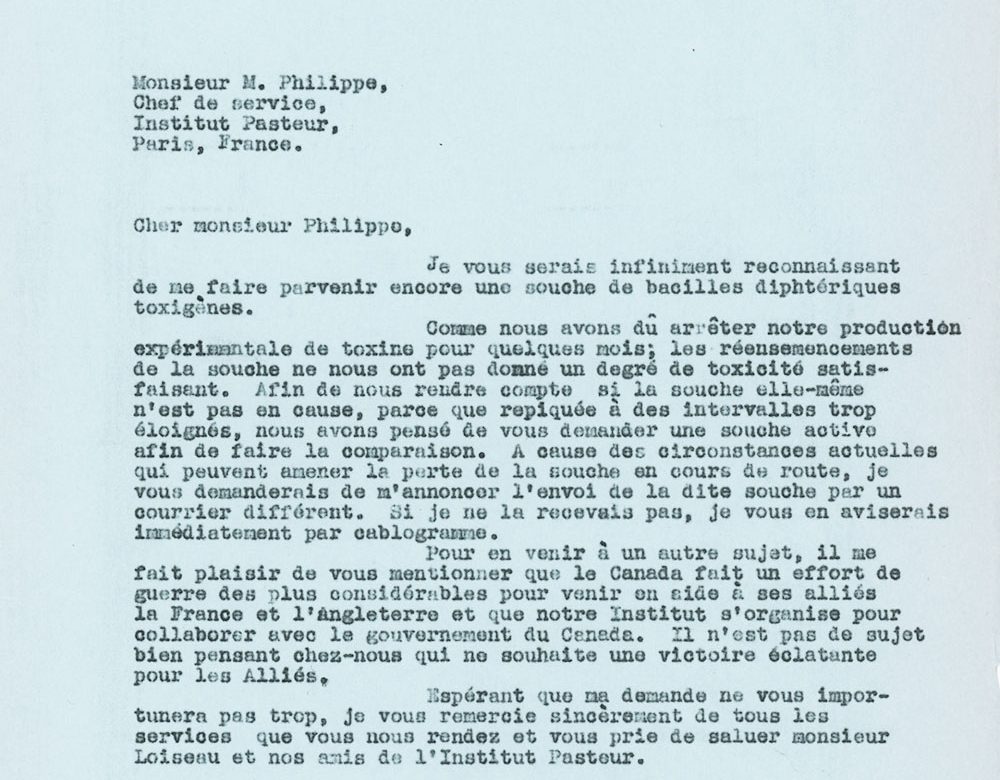

During the creation years of the Institute and later during the war, Dr. Frappier and the Institute of Microbiology opened relations with many other institutes and laboratories, especially from France and from the United States, such as the Pasteur Institute in Paris, which offered its support to the young Montreal institution.

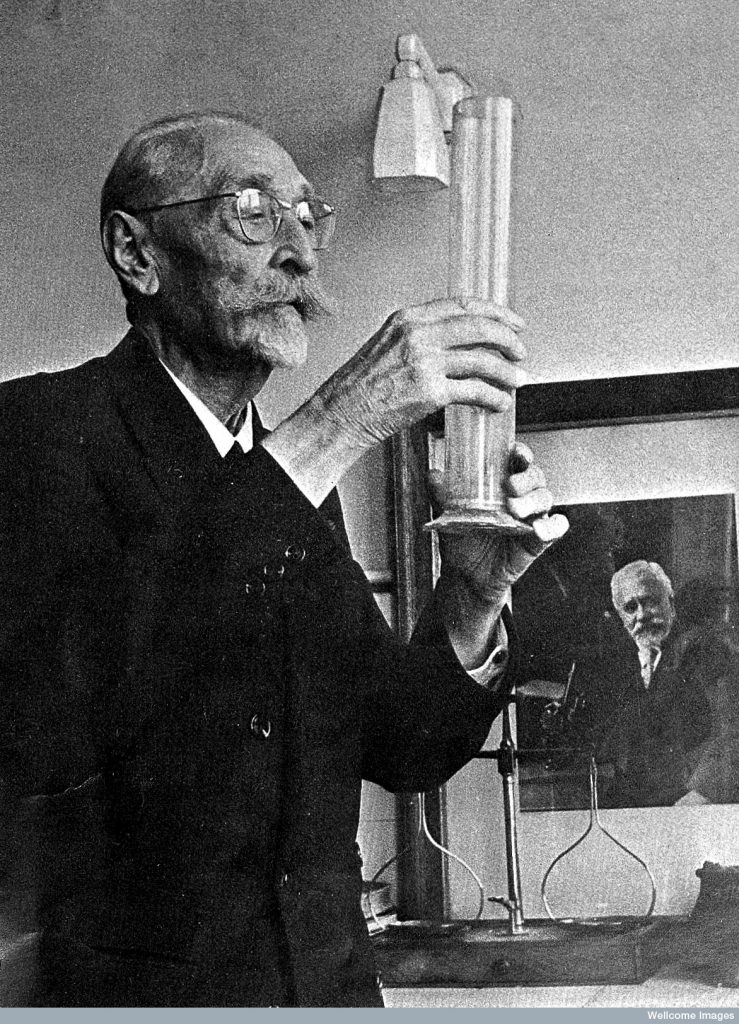

Indeed, Dr. Frappier and subsequently many of his colleagues from the Institute of Microbiology, went on to improve their skills alongside the famous discoverers of the BCG vaccine, Drs. Albert Calmette and Camille Guérin.

It was there, in Paris, that Dr. Frappier studied next to his mentor-to-be and future scientific advisor of the Institute, Dr. Léopold Nègre, and that he developed his unique expertise, combining Pasteurian and American knowledge to shape his future Institute of Microbiology.

The Pasteur Institute proved to be the very first model that inspired modern microbiology laboratories, such as the Institute of Microbiology. Like so, the Pasteur Institute established the basics of research in preventive medicine and public health, education and production of biological products. These were the pillars of the model created by Louis Pasteur in 1887.

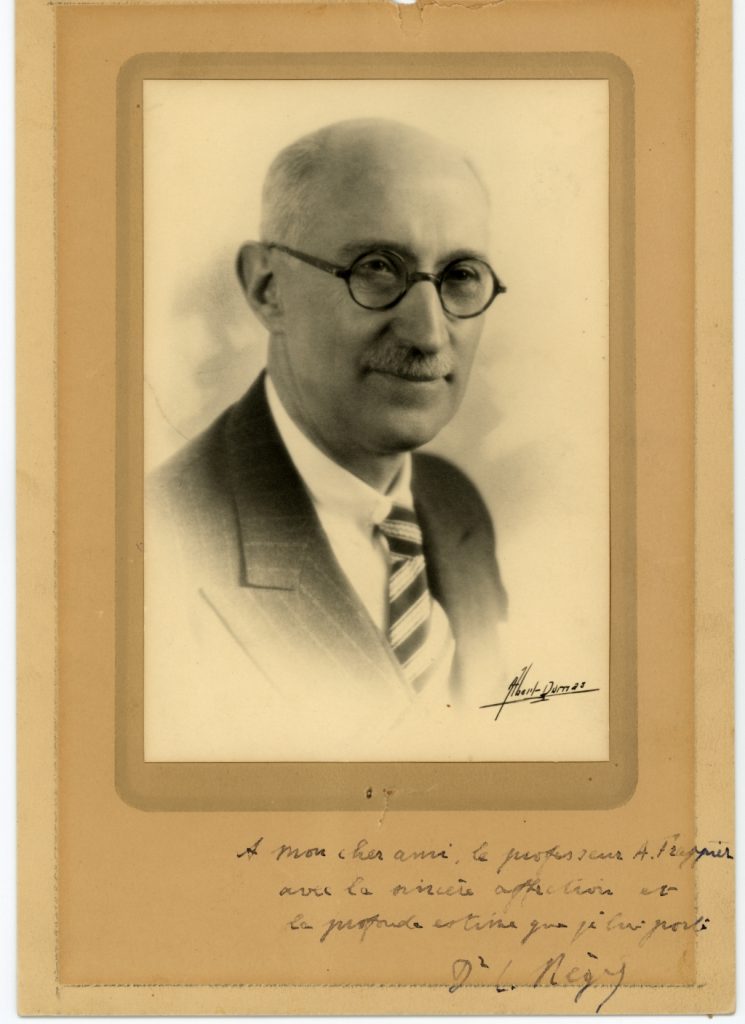

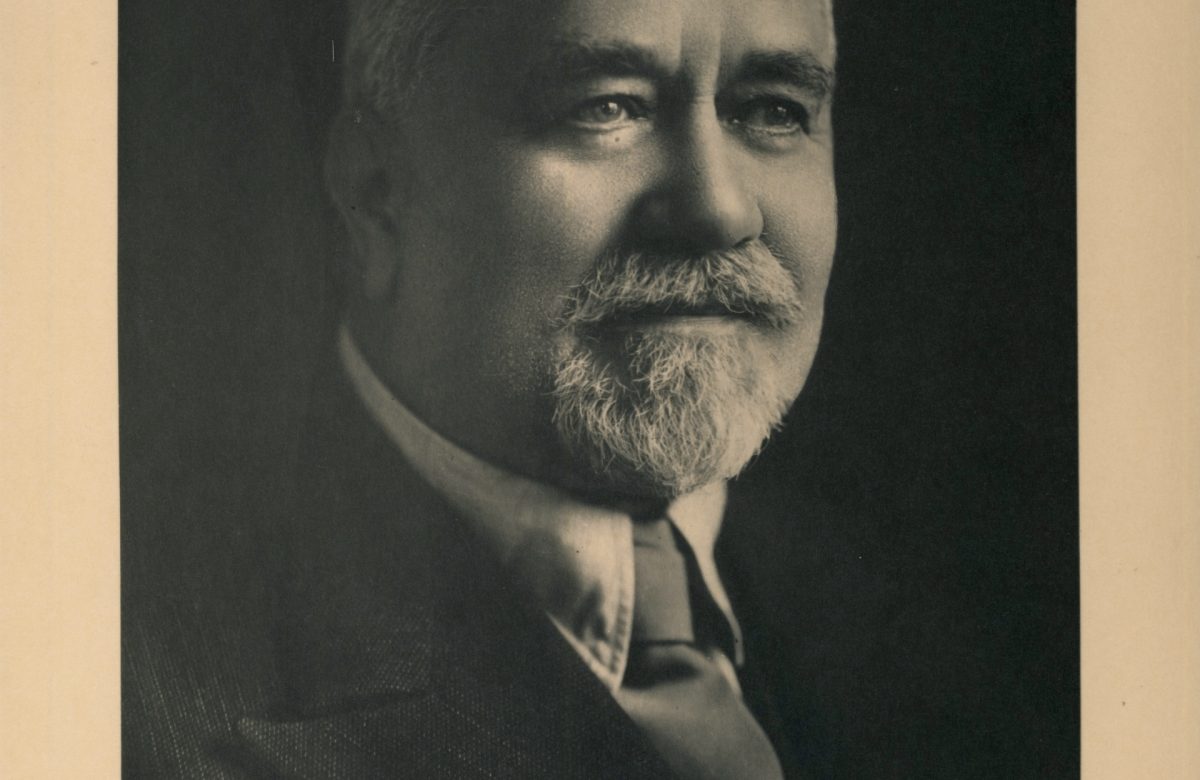

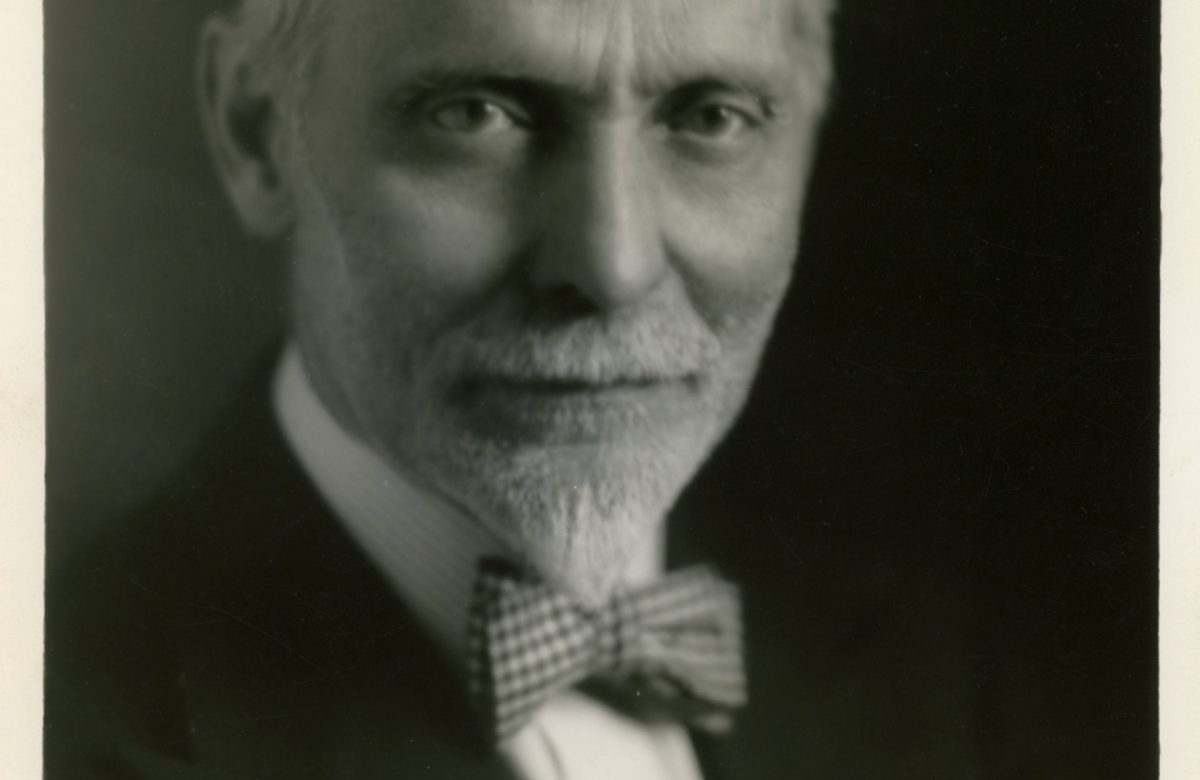

Dr. Camille Guérin (1872-1961), one of the discoverers of the vaccine against tuberculosis. Source : Wellcome Library, London Autographed photograph of Dr. Leopold Nègre (1879- 1961) of the Pasteur Institute, one of Armand Frappier’s mentors. Source : Armand Frappier Fonds Louis Pasteur and his wife. Source : Institut Armand-Frappier Fonds

Thus, the Pasteur Institute created close bonds within its community. The members of this great “Pasteurian family” maintained long lasting relationships and kept on sharing their knowledge. All through the war, Dr. Frappier benefited from got the support of other scientific partners, such as Dr. Denstedt from McGill University, who became technical advisor for the Serum Dehydration Service.

An international collaboration between experts was set into place, which enabled discussions on current studies during meetings of international committees. Furthermore, they shared their techniques and their methods for the greater good and the benefit of science. Internships and studying journeys abroad were examples of this international sharing. Members of the Institute of Microbiology spent time at Harvard University with Dr. Cohn, or at the Hygiene Laboratories of the State of New York. Likewise, the Serum Dehydration Service of the Institute of Microbiology took advantage of this team-work to improve its serum processing techniques.

The Human Serum Desiccation Service of the IMHUM

The Human Serum Desiccation Service was managed by Dr. Frappier and Jean Tassé and initially acted as a serum separation centre on behalf of the Connaught Laboratories. Thanks to continuous improvements and observation of various methods used in some American laboratories and at the Connaught Laboratories, Dr. Frappier and his team started to handle, by March 1944, the complete production of dried serum, processing blood donations collected by the Canadian Red Cross. Indeed, the first drying of human serum, conducted in Montreal, took place on March 29, 1944.

This was made possible by the dedication, and hard work of the experts from the Institute of Microbiology. They standardized serum processing methods and worked day and night, alongside with volunteers from the Canadian Red Cross Society to increase their production.

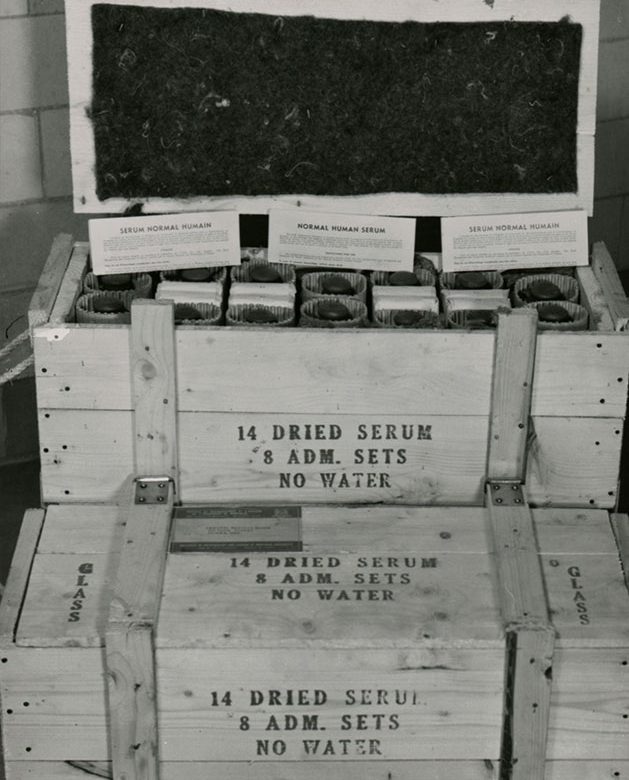

With their help, the Serum Desiccation Service shipped tens of thousands bottles of dried serum in more than 2,000 crates. Also, this would not have been possible without blood donors who massively contributed to the national blood donation program. Thanks to their generosity, more than two million blood donations were collected across Canada during the war. Their heroic gesture helped produce hundreds of thousands of bottles of dried serum that saved the lives of thousands of Canadian and Allied soldiers.

At the end of the war, all the facilities and equipment of the Human Serum Desiccation Service were donated to the Institute of Microbiology by the federal authorities. The unit that was once dedicated to the war effort headed towards serum fractionation, of which proteins such as gamma globulin were involved in the prevention of some diseases such as poliomyelitis and measles. The service was also employed to freeze-dry vaccines and antibiotics like penicillin, on behalf of pharmaceutical companies.

Processing of the human dried serum

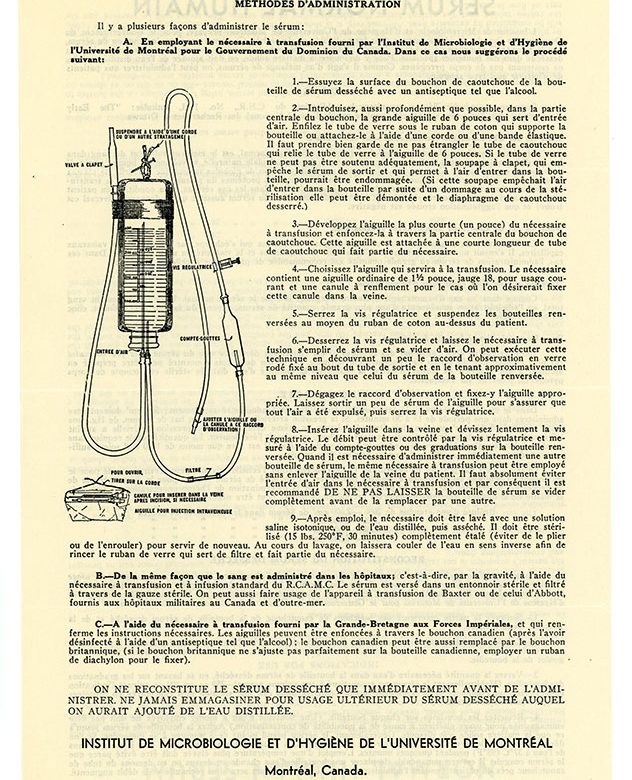

At the Institute of Microbiology, under the supervision of Dr. Jean Tassé, the Human Serum Desiccation Service brought together many areas of production, each one being a key step in the processing of dried serum. Thanks to the volunteers of the Canadian Red Cross Society, the process began with preliminary steps related to blood donations: preparation of sterile supplies required during blood donations (such as glass bottles), their expedition to the various Red Cross clinics and finally the return of bottled blood at the Institute of Microbiology.

After coagulation of the blood, serum can be separated from the plasma (the liquid part of blood) and blood cells (white cells, red cells and platelets) by means of centrifugation. The serum thus obtained from several donors was then mixed together and tested to ensure its sterility.

Next, the same serum was filtered, purified and detoxified to remove any remaining bacteria. Once again, sterility tests were performed. Only then, the serum could be transformed into its final dehydrated form. This phase began by bottling the serum and checking again for its sterility. The bottles, which were destined for the transfusion of the wounded, were frozen at low temperature (- 40 °C). At this stage, frozen serum could be stored for later use, or it could be dried using lyophilization or freeze-drying. A final round of sterility and toxicity tests was performed on dried serum before labelling and packing the bottles in wooden crates, along with all the necessary transfusion equipment. During the same process, additional crates were filled with bottles of sterilized water, which was used to reconstitute the serum to be transfused to the wounded. Dried human serum was then ready to be shipped to Allied forces on the battlefields.

Additional war productions and dispatching of biological products

Despite the war effort being a priority, the Institute’s researchers carried on their research in public health and preventive medicine, with a particular emphasis put on studies related to military medicine. Experiments were made on pyrogenic bodies which make human serum toxic, on gas gangrene and war wounds. They also studied the viral origins of cancer, as well as the various modes of vaccination for the BCG and allergies that this vaccine causes in some patients.

As a result, Dr. Frappier’s team developed other biological products in addition to human serum, such as diphtheria and tetanus toxoids, smallpox vaccine and penicillin.

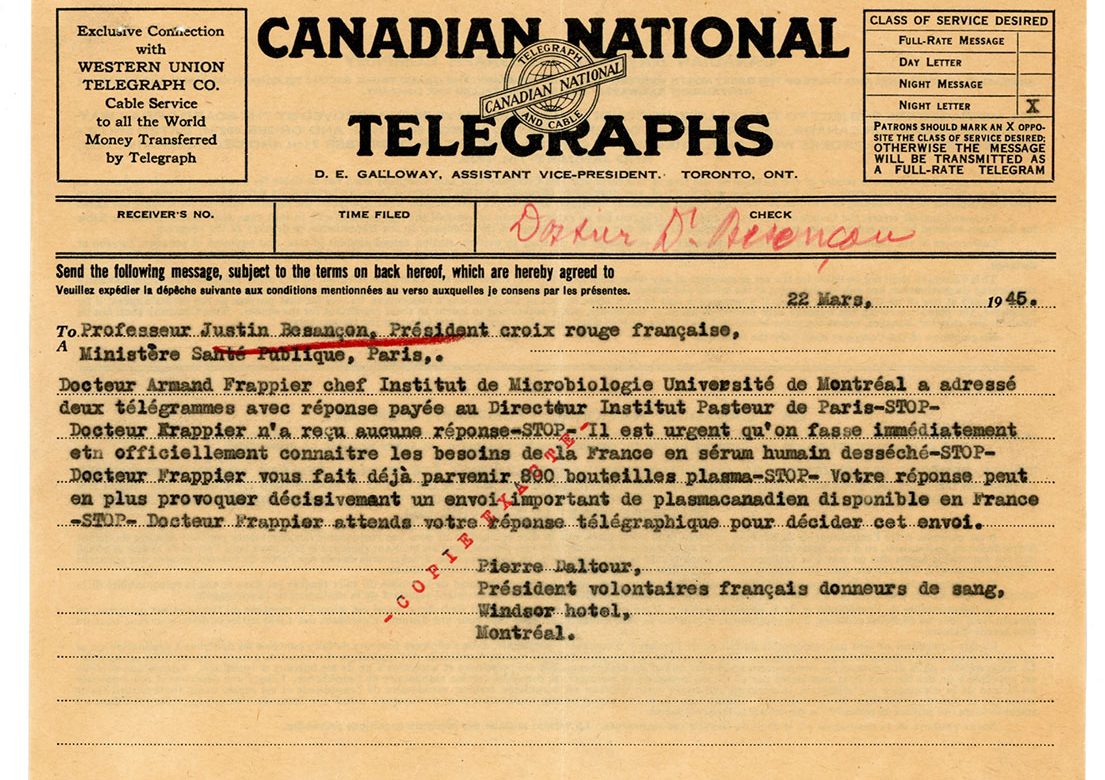

Varied buyers such as the departments of the federal and the provincial Health, Allied armies and even the Free French Forces, purchased these products. Thus, starting in 1941 the Institute of Microbiology dispatched vaccines and serums to the Province of Quebec, to Canada and to Europe. Exportation of biological products reached its peak at the end of 1944 with the shipments of dried human serum.

From that moment on, the Human Serum Desiccation Service worked tirelessly to catch up with the Connaught Laboratories so to send dried serum as quickly as possible to the injured. Thousands bottles of dried human serum were shipped to Europe, thanks to Canadian blood donors, but also to foreigners. For instance, in 1945, thousands of plasma donations from US citizens of the State of Vermont enabled the Institute of Microbiology to send more dried serum and plasma to combatants of the Free French Forces and Allied armies.

Through the cultural and historical affinities joining the French and French Canadians, Dr. Frappier also helped many wounded French soldiers with shipments of dried human serum to Dr. Mérieux at the Mérieux Institute in Lyon.

Post War : scientific advances and international recognition

In the postwar years, advances made by Dr. Frappier and his team helped to improve public health, especially in Quebec. Powered by the momentum given by its role in wartime, the Institute became a major player in the fields of research and education in microbiology and public health well beyond the borders of Quebec and Canada.

For the work performed throughout his career, Dr. Frappier would be honored time and again and became one of Canada’s most renowned scientists.

Improvement of Public Health and Preventive Medicine

As soon as the end of 1944, the Canadian Red Cross Society thought about the possibility to give all Canadian citizens free blood transfusions, for the blood donation program was so successful during the war. That way, everyone was to have access to this supply system in the country’s health care facilities who became part of the project.

However, at that time, the conditions in which blood transfusions were taking place were not appropriate. The process needed to be levelled up. And so, the Canadian Red Cross Society set up in October 1945 its national blood transfusion service and gradually established it in all the provinces.

First vaccination against influenza. Dr. Jean Tassé is being given the vaccine by his colleague Dr. Vytautas Pavilanis. The image was taken in the Laval laboratories in 1957. Source : Institut Armand-Frappier Fonds Photographer : André-Paul Cartier Early in the 1950’s, an expedition leaving for Saint-Augustin in the Gulf of the St. Lawrence River. The Institute sends a survey team led by doctors Vytautas Pavilanis and Jean Tassé to investigate an outbreak of poliomyelitis. Source : Institut Armand-Frappier Fonds. Photographer : Richard Arless Associates

Furthermore, physicians’ expertise such as Dr. Frappier’s was going to be well used to improve sterilization procedures that were employed by hospitals and clinics in Quebec. For these had many shortcomings during the war, so that in 1943, they were to blame for several blood and human serum contamination.

Then Dr. Frappier and some fellow doctors visited Quebec’s health care institutions to train hospital and nursing staff. They also took part in the standardization of sterilization methods in order to improve the provincial health care situation.

During the post-war years, the Institute of Microbiology transformed its war effort activities into peace time ones. For instance, the Human Serum Desiccation Service turned into a blood fractionation laboratory.

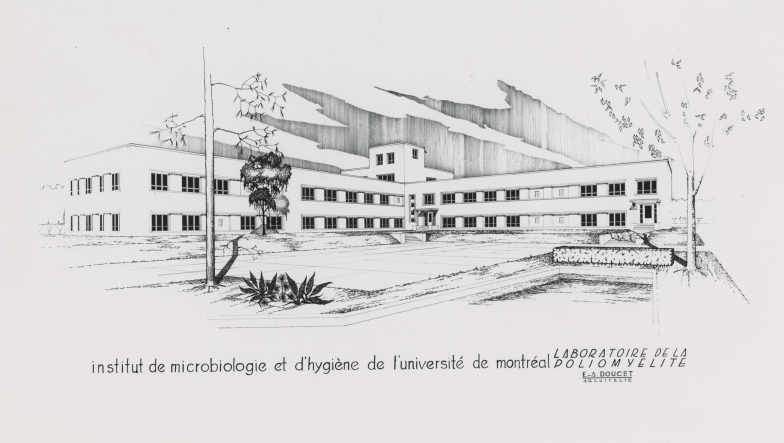

Dr. Frappier organized other laboratories oriented towards innovation such as the poliomyelitis laboratory that was inaugurated by the Premier of Quebec Maurice Duplessis. From this moment on, the Institute of Microbiology worked in many front line research projects in different fields such as virology or immunology. As for production, new vaccines were starting to come out of the Institute’s laboratories. Among other things were the Salk and Sabin polio vaccines and the influenza vaccine.

So then public health and preventive medicine in Quebec entered in a modern age.

Development and modernization of bacteriology in the province of Quebec

The scientific advances, which appeared during the war effort spanned during peacetime and arose in a common effort to improve public health in Canada and especially in the province of Quebec. This prevailing trend of social and health reform urged Quebec to take some measures to be up to date.

It expressed itself in numerous projects such as the idea of creating a school of hygiene within the Institute of Microbiology. Dr. Frappier, as well as several influential public characters (Montreal Chambers of Commerce, Provincial Health Minister Paquette), were at the root of this project. According to them, Quebec needed to provide healthier environments. It was also necessary for the province to be self sufficient in the making of biological products, required by sanitary imperatives. Furthermore, it was necessary for the province to be able to train its own scientists instead of letting them study abroad (United States or Toronto).

Dr. Armand Frappier vaccinating a child during a mission to fight tuberculosis among the Cree Nation of the Mistassini region. 1948. Source : Institut Armand-Frappier Fonds The hygienists practical work laboratory at the University of Montreal School of Hygiene. 1945. Source : Institut Armand-Frappier Fonds. Photographer : C. A. Barbier

Therefore, establishing a specialized teaching of public health and preventive medicine was going to bring forth many benefits for the province.

First of all, teaching at the School of Hygiene was to be in French and new scientific and technical careers were to be created in order to modernize the Quebec scientific landscape.

Then, these experts were to produce exactly what the province needed for its public health measures. Moreover, all the profits from the sale of biological products were to be “sent back to science” to help research and education.

The School of Hygiene thus fell within the modern microbiology movement initiated by the Pasteur Institute of Paris. The founding of the School of Hygiene fulfilled some of the goals set by the Institute of Microbiology, namely, make the province more economically autonomous in science and stimulate specialized teaching. Besides, the school’s will was to promote French-speaking scientific careers and to strengthen French-Canadian expertise.

The School of Hygiene was founded at the end of 1945 with the agreement of the University of Montreal and the financial support of the provincial government. It began to be operational in 1946. Dr. Frappier was to be dean of the school from 1945 to 1965 and the Institute of Microbiology provided premises and experts for teaching and research.

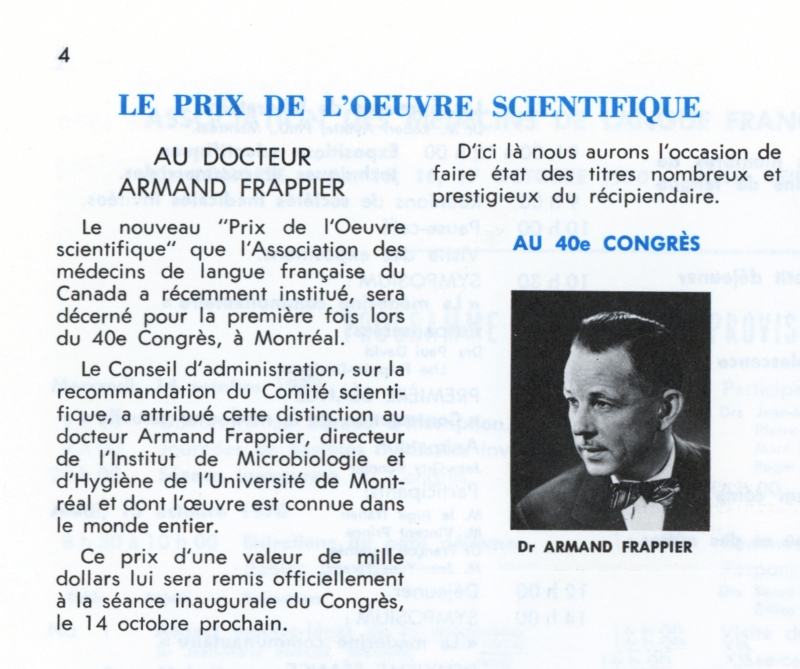

Accolades for the work of Dr. Armand Frappier and the Institute of Microbiology and Hygiene of the University of Montreal

In the years after the war, the work of the Institute of Microbiology and Hygiene of the University of Montreal had already echoed beyond the borders of Quebec and Canada. Thanks to the role played during the Second World War, the Institute started to weave a large network with public agencies both here and abroad or with research institutions such as the Institut Pasteur or the Connaught Laboratories of the University of Toronto.

This young institution gathered a lot of attention. In a letter written in 1945, Frappier admitted that “not a day goes by without welcoming some distinguished visitor.” The Institute’s war effort contributed, without a doubt, to its success and put it in a privileged position towards the Allied governments. However, its visibility was mainly the result of the efforts of its dynamic director.

Helped by a loyal team of associates, Dr. Frappier saw his Institute quickly becoming a major player in preventive medicine and public health research.

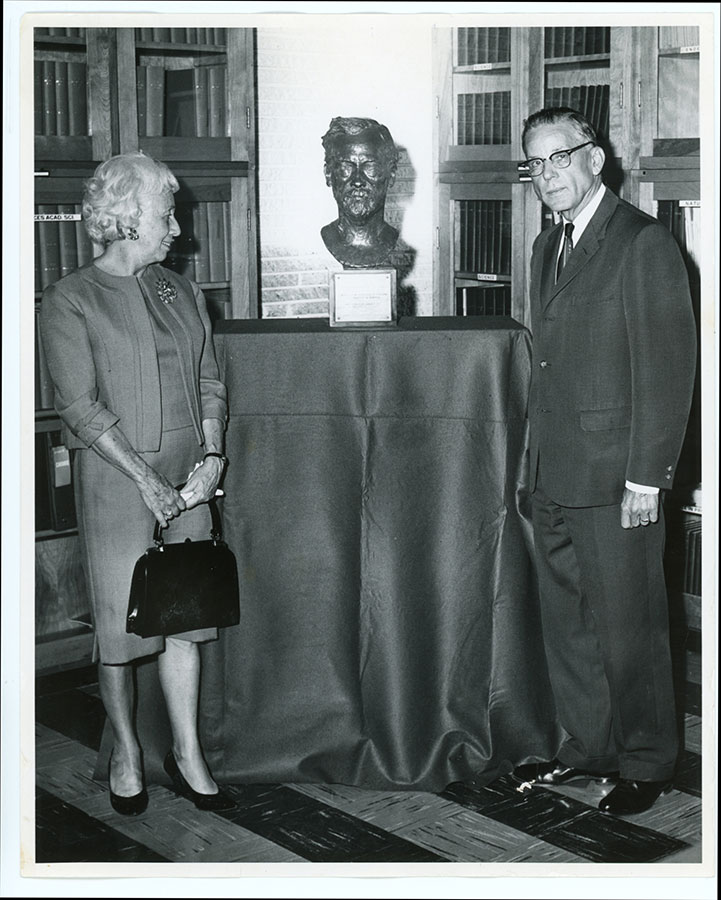

At a reception in his honour, Armand Frappier shows the Order of Canada certificate he received in 1969. He is seen with his colleague Victorien Fredette and is wearing the medal of the Order. Source : Institut Armand-Frappier Fonds Armand Frappier being awarded a bronze bust of Louis Pasteur. Standing next to him is Thérèse Ostiguy, his wife. The bust is one of very few copies authorized by the Pasteur family. September 9, 1964. Source : Institut Armand-Frappier Fonds

As director of the Institute, Armand Frappier sat on numerous committees, such as the National Research Council of Canada, as a member of the Advisory Committee on Medical Research. Most notably, he became a key expert in the fight against tuberculosis, working amongst others with the World Health Organization. He was the guest of many scientific meetings around the world, such as conferences in prestigious medical academies in France, Poland, Germany and Hungary.

From early in his career to his last days, Dr. Frappier earned many honours for his pioneering research in microbiology and for improving public health. He was the recipient of fifty medals, such as the Order of the British Empire, of honorary degrees from major universities, of recognition like the Prix Jean Toy Price from the Académie des sciences de France. He was also named “Great Montrealer” in the field of medicine. The governments in Quebec and Canada also acknowledged his contribution by naming him Companion of the Order of Canada (1969) and Grand Officer of the National Order of Quebec (1985).

The recognition and honours received by Armand Frappier bore eloquent witness to the mark he left in history as one of the greatest scientists of the twentieth century in Canada.

Credits

- Project coordination : François Cartier, Archivist at Service des archives et de la gestion documentaire

- Texts, translation and revision : Laura Rosello, François Cartier

- Image digitization : Laura Rosello, François Cartier, Pierre Payment

- Web integration : The Service des communications et des affaires publiques

- Archives arrangement : Laura Rosello, François Cartier, Caroline Charette, Marilou Fortin, Catherine Dugas

- Scientific advisor : Professeur Pierre Payment

Thank you to

Library and Archives Canada, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, Michel Fortin and Maude Côté at INRS, the Armand-Frappier Museum, Guylaine Archambault and Martine Isabelle, the Fondation universitaire Armand-Frappier, the Canadian Red Cross Archives and M. Robert Gourgon, the Division de la gestion des documents et des archives of the University of Montréal, Diane Baillargeon and Monique Voyer, the University of Toronto Archives. This virtual exhibit is possible thanks to the financial aid of Canadian Heritage and the World War Commemorations Community Fund.

The arrangement of the Armand Frappier Archives was made possible thanks to the financial aid of Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec and its Soutien au traitement des archives Program.