- Overview

The series “Tour d’horizon en trois questions” highlights research in all its forms and takes an informed look at current events.

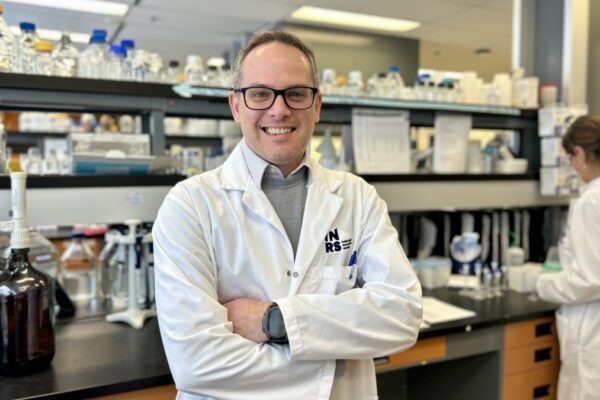

Jean-François Naud, professor and director of the Laboratoire du contrôle de dopage

With the Milano Cortina 2026 Winter Olympic Games around the corner, the issue of doping in sport is once again in the spotlight, reminding us of a challenge inseparable from high‑performance athletics. Despite decades of vigilance, cases of athletes using prohibited substances continue to make headlines and test the integrity of competitive sport.

For more than 50 years, the Laboratoire du contrôle de dopageat Institut national de la recherche scientifique (INRS) has played a central role in this fight. Headed since 2023 by Professor Jean‑François Naud successor to trailblazer Christiane Ayotte the laboratory continues its tradition of scientific excellence thanks to a team of about thirty specialists in chemistry, biochemistry, and biology dedicated to improving methods for detecting doping in sport.

Professor Naud is a globally recognized expert whose research focuses on proteins and peptide hormones, including erythropoietin (EPO). We met with a researcher committed to defending clean and fair sport—both in Québec and internationally.

What role does your laboratory play in the Milano Cortina Winter Olympics and in the analysis of sports samples in Canada and abroad?

Our laboratory is not directly involved in analyzing samples collected during the Milano Cortina Olympic Games. However, many Canadian athletes—as well as athletes of other nationalities—who train or compete in Canada will undergo doping tests before their departure. These samples will be analyzed in our facility, as we are the only laboratory in Canada accredited by the World Anti‑Doping Agency (WADA). In addition, some members of our team will join the Rome anti‑doping laboratory to provide technical support and expertise during the Games.

Each year, we analyze approximately 20,000 samples. In addition to athletes from the roughly 70 national organizations that have adopted the Canadian Anti‑Doping Program, our expertise is sought by the WNBA, NHL, ATP, MLS, and CFL, as well as by international events such as the Pan American Games and the Central American Games. We also collaborate with several national anti‑doping organizations, including in Guatemala, Jamaica, the Caribbean, and Central America.

Apart from day-to-day sample analysis, what other activities stem from your expertise?

Our mission encompasses all activities tied to anti‑doping efforts. As a member of WADA’s Laboratory Expert Advisory Group, I provide specialized advice, recommendations, and scientific support to WADA leadership. I also report to the Health, Medical, and Research Committee on management of the accreditation and re‑accreditation process for anti‑doping laboratories worldwide.

The Advisory Group is also responsible for updating the International Standard for Laboratories (ISL), which ensures the validity and harmonization of results produced by accredited laboratories. Several members of our team also contribute to WADA working groups responsible for drafting technical documents that govern analytical procedures.

Our expertise is frequently required in arbitration cases, particularly to assess athletes’ explanations regarding the presence of prohibited substances. We also advise various anti‑doping organizations on managing atypical findings, whether they come from our laboratory or from other accredited laboratories.

Maintaining this level of expertise depends on research, which is essential for identifying new metabolites, detecting emerging substances, and developing novel analytical methods. Close collaboration with the pharmaceutical industry enables us to anticipate the misuse of legitimate medications and identify athletes who abuse them.

What are the main current and future challenges in the fight against doping?

Despite significant progress, some doping methods remain difficult to detect, such as autologous blood transfusions, in which an athlete reinjects their own blood to artificially increase red blood cell mass. The Athlete Biological Passport (ABP) can detect certain manipulations, but it can be influenced by many factors, underscoring the need for continued research.

The arrival of more sensitive detection instruments represents a major breakthrough: they can identify extremely low concentrations of prohibited substances. This increased sensitivity widens the detection window but also reveals traces linked to unintentional contamination—an argument increasingly raised in arbitration. While some cases can indeed be explained by contamination, not all positive results can be justified this way. It is therefore essential to study potential contamination levels in athletes, as well as the presence of substances in certain foods, supplements, or products depending on the region of the world. This issue affects both anti‑doping efforts and public health.

Athletes must also acknowledge their responsibility when they voluntarily expose themselves to contamination risks, including through intimate relationships with individuals who use prohibited substances.

Lastly, we must reflect on our expectations of sport, whether recreational or competitive. The announcement of the first Enhanced Games, scheduled for May 2026 in Las Vegas, challenges the value of healthy and fair sport by proposing to normalize—or even promote—doping to maximize performance. Athletes are models of perseverance: do we want them to break records at the expense of their health, or push their limits while respecting their physical and psychological integrity?